An eye for detail

A frequent sojourner to the Islands, Bessie Beckett wrote insightful observations of their life and traditions

Women Travellers in Catalan Lands

We went second-class as being much more festive and amusing, and the carriage was soon filled with people all intent on holiday making. The older folk were discussing the probable prices of turkeys in the Christmas market.

It was fairly dark as the train contoured the mountain-side; but each time we emerged from one of the tunnels dawn seemed nearer. At last, at the other end of the long tunnel, on leaving the mountains behind us, we saw that most of the stars had grown paler, and the sun was just rising, rosy and full of glory[...]

Here, as in the East, the shepherds lead their flocks, and call to them from time to time. As it was a cold morning, the men wore rough goat-skins round their shoulders, and the whole scene was so absolutely Oriental that the picture must have come very near to that of the other occasion when shepherds had been watching their flocks.

I shall never hear that part of the Messiah again without visualizing that dawn. Always the movement of the violins in the prelude to that recitative will mean for me the twinkling of the stars, and the clear soprano will recall the breath of fresh morning air.[…]

By the time that the little train drew up carefully beside the Palma platform, the world had once more become normal. The bustling crowds surged into the street, and there was a holiday appearance everywhere.

Just once a year a special market is arranged for the sale of turkeys, lambs, rabbits, piglets, chickens, and pigeons. It is, indeed, a quaint sight. Rich and poor, old and young, collect to buy their Christmas dinners. Like all the other animals, the turkeys are sold by live weight; then, with a string tied round one leg, they are driven to their final homes by small children. If it is far the wretched bird sits down to rest several times en route, and later in the afternoon, if one walks along almost any street, one is pretty sure to see the tethered birds on every balcony, and to-morrow the black feathers will be fluttering down from the windows, for the Mallorquinas kill and cook before the body is cold[...]

Midnight Mass, in Mallorca, is a special service, peculiar to the island. We had been advised to be in good time if we wanted places where we could see and hear; so, wrapping ourselves up warmly, and armed with our camp stools, we arrived at the cathedral at about half-past ten. By eleven the building was packed, but the congregation was reverent and well-behaved. I gave a helping hand to an old woman who wished to take up a place under the pulpit. I passed her stool along and handed her on. She stood still to say “Thank you! God will reward you soon” –a sentiment I welcomed warmly, as she was standing on my foot, and was no light weight. However, we all settled ourselves in good time, and listened to the service which was being intoned behind the High Altar. Nobody could follow it as it was too dark. Even in the Cathedral the atmosphere seemed misty, and the altar and chancel were still unlighted.

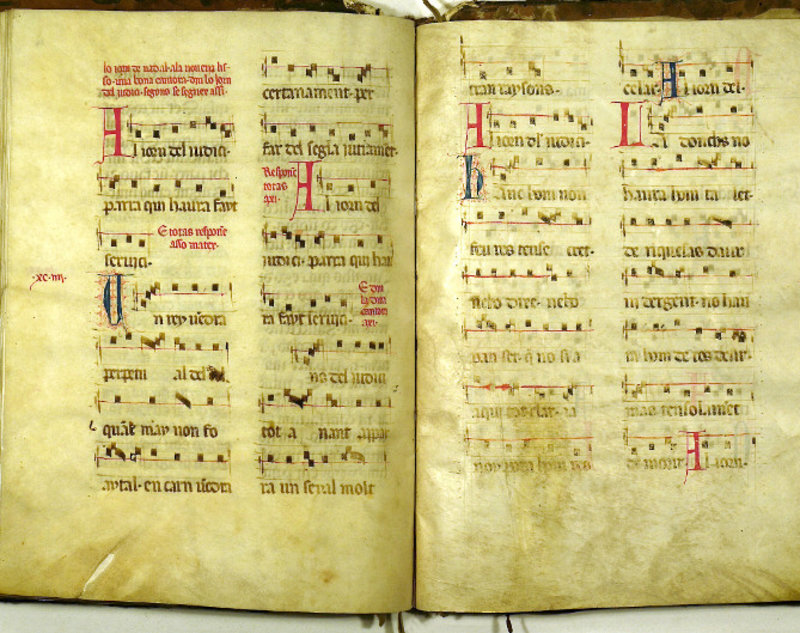

Then there came a sound of shuffling feet and dimly I made out a little procession of three boys, two of whom bore lighted candles, and the middle one, dressed in pink and white and gold, carried a sword which he held upright in front of him. The three passed up into the Gospel pulpit, and a moment later the organ began playing a sort of little prelude. At the end of it the boy with the sword began his song. He had the usual husky and nasal tone which is produced throughout the Island, and to my mind is the most unmusical of human noises.

The Sibila is so old that its origin is lost, and it is only of recent years that any attempt has been made to trace its history. The words are sung in Mallorquin, and have been translated into English by one of the Cathedral priests and copies can be easily bought in Palma.

The singing is timed to end just at midnight, and ends with a joyful burst of staccato just as the lights are turned on with a flash, and then the mass begins.

I could not help being amused at the way so many girls turned to look up at the chandelier hanging in the nave, and counted the discs of rice paper suspended from it. This is also a local custom to show the number of Sundays before Easter; but I do not know why this interests them because the Island people are exempted from fasting—a reward for their good services in the Third Crusade.

Bessie Beckett

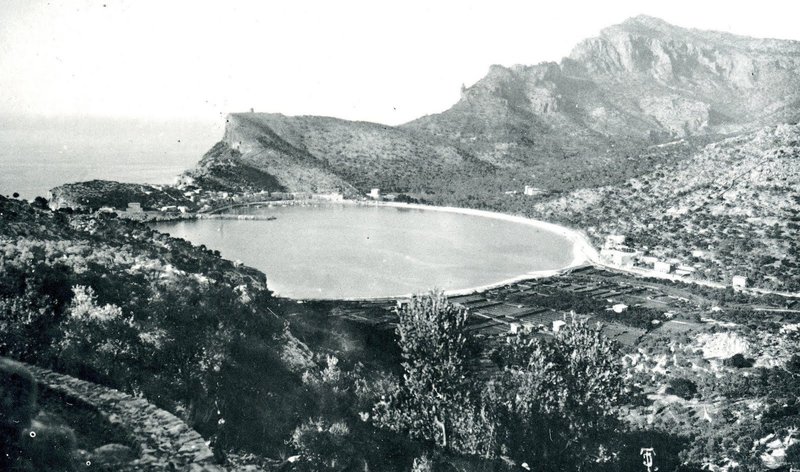

Bessie Beckett (1870-1947) was one of the six children of Major-General Charles Simeon Thomason and his wife Ellen Fanshaw Dundas Drummond. Though born in the Scottish Highlands, she spent a significant part of her life in India, where several members of her family had been fully devoted to imperial service. In 1889, she married William Thomas Clifford Beckett, an Indian Army officer and railway engineer who would reach the rank of Brigadier General. The birth of their two sons (who also pursued a military career, distinguishing themselves in both world wars) enabled her to renew the ties with Scotland, as the family returned there for their education. In the 1920s, after the husband's retirement, the Becketts found a house of their liking in Sóller, Mallorca, where for over a decade they spent several long sojourns. The minutiae of such vacations on the island are collected in her only book, Memories of Mallorca (1947), which contains character sketches, transcriptions of local folk songs and details on some of the main seasonal events celebrated there. One of these, reported in the given passage, was the orally-transmitted “Song of the Sybil”, an anonymous liturgical drama describing the Apocalypse and announcing the birth of Christ, which had been performed in Mallorca and other Catalan-speaking territories since the Middle Ages. Beckett, who had received musical studies, cannot help criticizing the performance.