Poetry and revolution

A new exhibition running at Barcelona’s Picasso Museum until March 15 traces the deep friendship between the great artist and the surrealist poet Paul Éluard, the man who awakened Picasso’s political conscience

It might be a push to say that if Picasso had not been friends with the poet Paul Éluard he would never have painted Guernica. Yet, what is not in doubt is that Éluard was the person who awakened Picasso’s political conscience. He shaped him ideologically along with Dora Maar, the most intellectual of the Malaga-born genius’ wives, and it was Éluard who introduced them in 1935.

It’s a good thing that, rather than offering irrefutable truths, exhibitions should pose possibilities not considered before, and that is something that Pablo Picasso, Paul Éluard, una amistat sublim (A sublime friendship), which runs at the artist’s museum in Barcelona until March 15, does extremely well.

Picasso loved poets. And it is well-known that love is an inspiring force. Picasso met Éluard when he was still getting over the death of his first poet friend, Guillaume Apollinaire. In fact, it seems the two met for the first time during a performance of a play by Apollinaire, in 1918.

Éluard was a young man of 23. It did not take long before he began collecting the works of the painter (14 years his senior) at bargain prices, which he would then often resell. Picasso was well aware of this, and yet he still gifted him many of his works.

“Picasso was always very generous towards his friends,” and even more so towards those he knew were struggling to survive on their own creations, says Malén Gual, conservator at Picasso’s museum and curator of the project along with the institution’s director, Emmanuel Guigon. The exhibition is filled with pieces from the poet’s collection, including the vibrant collage of the woman’s bust owned by the Catalan collector, Josep Suñol.

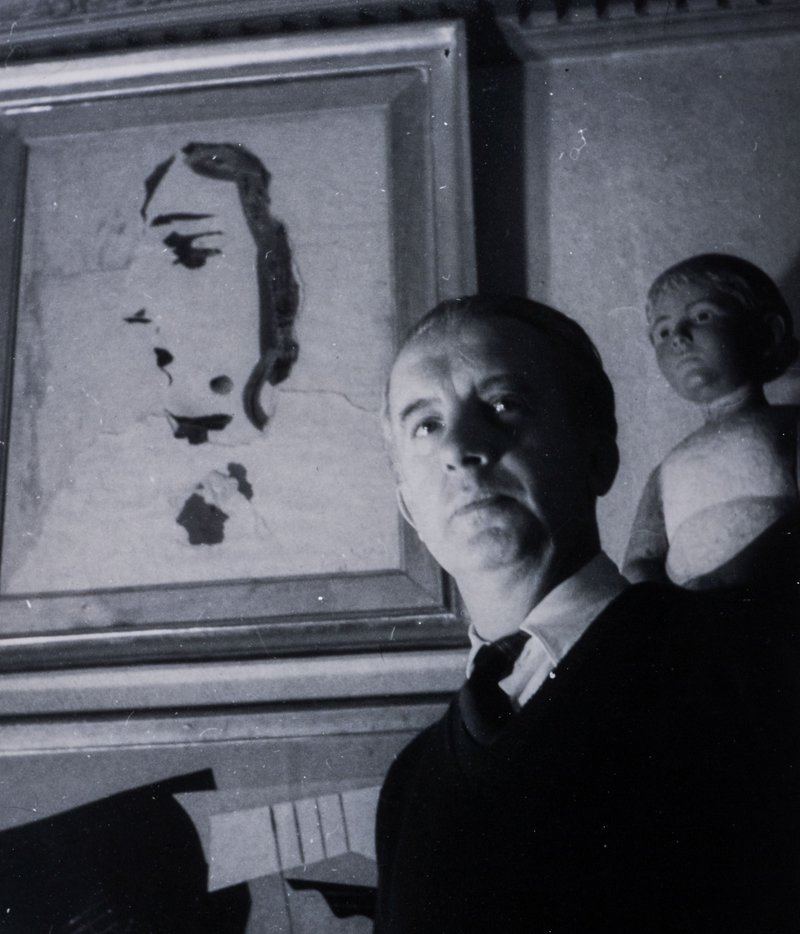

It includes the first portrait of Éluard, which Picasso gave him in 1936 and the poet exultantly showed off all over Barcelona. The artist, who by this time had become the god of art, sent Éluard to represent him at the exhibition devoted to him by the Adlan group just before the Civil War broke out. The poet then moved to Madrid, where he suffered the bombing by Franco’s air force. Seeing the people at war against fascism led him to write his first clearly political poem, November 1936, which motivated Picasso to conceive of the series of prints, The Dream and Lie of Franco.

The bête noire of Francoism that Picasso became until his last days had been born. His internal rage found an escape route in his painting Guernica. When it was unveiled at the Republican pavilion of the Paris International Exposition in 1937, Picasso had the painting shown alongside Éluard’s poem, La victoire de Guernica, which in this case had been inspired by the artist. “They mutually enriched each other,” says Gual.

Politics is an extremely important concept in this exhibition, although it is mixed with others. Love, embodied by Dora Maar, who Picasso painted during the Second World War with deformed facial features and even skulls (there is a never-before-seen sketch book in the exhibition that makes one’s hair stand on end). It is the face of the horrors that were destroying Europe. Yet, love is also embodied in Nusch, Éluard’s second wife (his first was Gala, who left him for Dalí), and while there is nothing to prove that she became Picasso’s lover, he painted her with the same intensity as if she had been. The proof of the intimacy between the two couples is hidden in the erotic photos of their summer holidays in the south of France. Let each interpret how they will what love meant to them, but it was nearer the freer end.

Friendship, love, politics and art. A lot of art. Éluard blistered his fingers writing poems to Picasso. “To you, Pablo Picasso, my sublime friend,” is the line from which the exhibition’s title is taken. And Picasso never tired of illustrating his friend’s books and painting his portrait. And that was how it continued until the end. It was a premature end for Éluard, who died in 1952. Nusch had already died in 1946. The poet married his third wife in 1951. Picasso gave them a precious wedding gift, a giant vase decorated with dancers and musicians. And this is what brings the exhibition to an end.

Yet, in a way, it doesn’t finish here. It continues in another that is separate but closely connected: Picasso poeta (Picasso the poet) is being held at the museum until March 1, and focuses on one of the artist’s least known facets. His poetic side manifested itself from the 1930s, coinciding with the time when his friendship with Éluard became deeper. “Ultimately, all of the arts are one. A painting can be written with words, as feelings can be painted in a poem,” said the artist.

“At heart I am a poet derailed,” he once confessed. In fact, his interest in writing dated back to when he was a teenager. “On many of his drawings from his formative years, many of which we have in the museum, there are inscriptions that we have to see as the root of Picasso the poet,” points out Claustre Rafart, conservator at the Picasso Museum and a member of the team that curated this exhibition that, as with the one about Éluard, is also due to a close collaboration with the Picasso Museum in Paris.

art