Maspons the useful

MNAC national gallery has major retrospective of Catalan photographer’s work, with 500 of his images, including some that have barely or never been seen before

More than taking them, what excited Oriol Maspons (Barcelona, 1928-2013) most was seeing his photographs published. He didn’t take photographs for the pleasure of it; they had to fulfil a purpose or provide a service. Once done, he lost interest in them and would already be thinking about the next project. This helps explain the chaos of his archive, which resembled a rubbish dump. “He gave them no value. For him, they were even something of a nuisance,” says his son, Àlex. Fortunately, one of his closest friends was David Balsells, who founded the photographic archive at the MNAC national gallery. During one of their weekly lunch dates, Balsells convinced Maspons that the best place for his archive was in Catalonia’s foremost public art gallery.

It is ironic that the work of the person who fought the most to free photography from its conventional pictorial tics should end up in a temple devoted to painting. Yet, Maspons died in 2013 happy with his decision, apart from the caveat he would never tire of explaining to gallery director Pepe Serra when they met. Whenever his work was put on display, he wanted it to be clear that it was the result of a commission, for a book, media report, album cover, ad campaign, or film promotion.

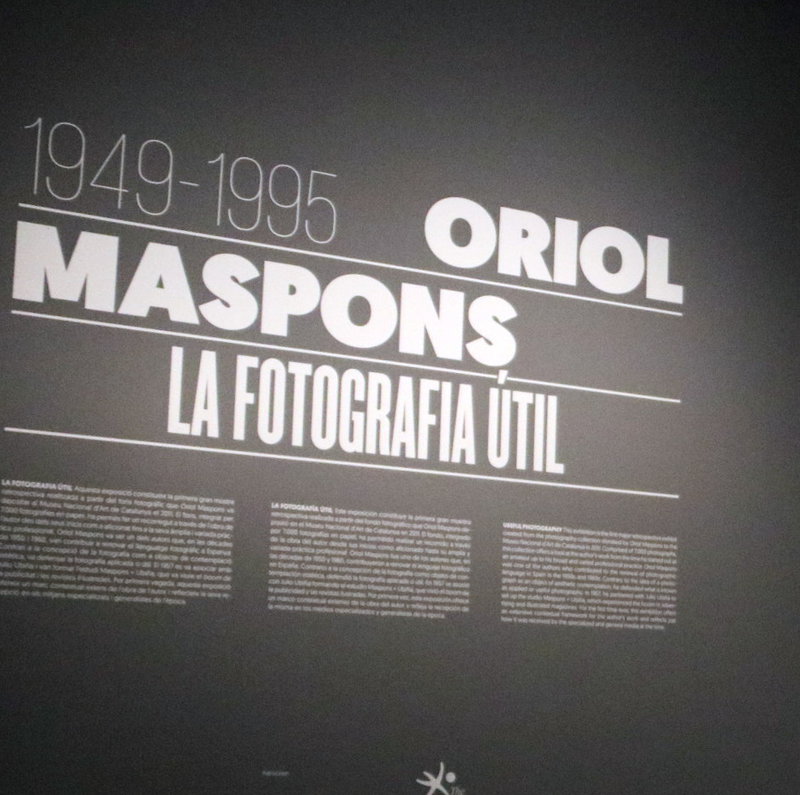

Above all, Maspons wanted to be a useful photographer, and ’useful photography’ is the title of the exhibition at MNAC that is the culmination of the adventure to safeguard the legacy of one of Catalonia’s foremost creators. Oriol Maspons, la fotografía útil / 1949-1995 runs until January 12 and brings together 500 photographs and 200 items of documentary material. It is a lot to get through, but if a single visit is not enough, the entrance ticket can be reused.

However, the major retrospective comes late. Too late for Maspons to see it, and too late for Balsells, who is retired and in delicate health, to curate it. That job has been done by Cristina Zelich, who has brought all her experience and sensibility as a photographer, critic and curator to the task of sorting through an ocean of 7,000 photographs.

The easiest thing would have been to stick to Maspons’ most iconic photos, which we have all seen a thousand times, such as the image he took for the cover of Juan Marsé’s novel, Últimas tardes con Teresa, those he took of the first bikinis to be seen on the beach, those of the members of La Nova Cançó and, obviously, those of his group of friends, the Gauche Divine. Yet, that was not enough for Zelich, who insists: “Maspons is much more than the photographer of the hippies in Ibiza or of the Gauche Divine.”

Bipolar photography

The exhibition immerses the visitor in a career that is much richer and more complex, which gestated in the 1950s when the debate on the nature of photography and its bipolar character of being both artistic and practical. Although Maspons joined the Agrupació Fotogràfica de Catalunya, he soon came to oppose what he called ’salonism’, characterised by incestuous amateur contests with rules that limited individual genius. The association expelled him.

“He wanted to be a professional photographer,” says Zelich. But that was just a dream in the cultural desert of Franco’s Spain. So he went abroad, to Paris, where he befriended Henri Cartier-Bresson, and to London, with his master: Francesc Català-Roca.

In 1957, he began to associate with fellow photographer, Julio Ubiña, and started developing his ideas of modernity, which can be summarised in one concept: photography had to “recount its time”. He left a deep imprint on the photography scene of the second half of the 20th century, both on his contemporaries and on the new generation of upcoming photographers. And not only in practice but also in theory. One aspect that the MNAC exhibition shows is Maspons the thinker. “He wrote very well,” says the curator, and his writings will be compiled and published by the museum in the autumn.

Zelich has dug up some hidden gems from the archive. On the one hand, forgotten material and, on the other, never-before-seen material, such as the failed book the photographer aimed to do with poet José Agustín Goytisolo about Cuba during the height of its revolutionary fervour in 1967. The images are extraordinary, but it was never published because Maspons did not like the text Goytisolo wrote.

There was another episode in 1967. Esther Tusquets’ publisher, Lumen, had asked him to advise on publishing the book Nothing Personal by James Baldwin and Richard Avedon, but his advice was ignored. Hurt, he and other photographers published a signed ad in the magazine Destino, criticising the indifference shown towards a masterpiece dealing with the US’ racist and classist system.

Feminist protests

Exhibitions often leave out the darker side of artistic careers, but MNAC has a room reviewing Maspons’ work with Interviú magazine. For a report in the 1970s, he ran an ad in La Vanguardia looking for women who had been raped and left pregnant. Feminist groups protested outside his study. “He wasn’t bothered,” says his son, who confesses that his father used him when he was small for “gonzo” articles. At the time he cried, but today he remembers it with a smile.

art