Jujol, the origins

A new artistic route invites visitors to discover 16 works, most of which are now little known, that represent the legacy left by Catalan architect Josep Maria Jujol in his native region of Camp de Tarragona

The architectural legacy of Josep Maria Jujol (Tarragona 1879-Barcelona 1949) is highly fragile. Yet, he understood wear and tear as just another aspect of his work. Jujol always saw the passage of time as an ally. There is an anecdote that reveals his radical vision. During the Civil War, a fire was lit in the Sagrat Cor church in Vistabella. The arsonists used the pews to build a pyre (the floor still shows the traces of the scorching) and the smoke and flames blackened the walls of the nave painted by the architect himself. Once the conflict was over, he was asked about reversing the damage but made it clear that he had no intention of doing anything about it. “What the reds did in three years, time would have needed 40,” he said. In fact, when a rich man in town had the walls whitewashed for his daughter’s wedding, Jujol was furious and never returned to Vistabella.

He was certainly a character, and unique among modernist architects, something that is not noted enough. Professor of architecture Roger Miralles points out that Jujol’s work remains generally unknown: “Everyone, including architects, only think about three or four of his buildings, especially those in the Barcelona area: Can Negre and Casa dels Ous, in Sant Joan Despí, and Casa Planells, in the capital.” We all know that Antoni Gaudí casts a long shadow, and the other thing Jujol is known for is his work with the celebrated creator of the Sagrada Família.

Yet in the Camp de Tarragona area he left a mark that amounted to over 60 works. There he is saved from oblivion by Casa Bofarull in Els Pallaresos, Tarragona’s Teatre Metropol and the church in Vistabella mentioned above.

Yet the problem with Jujol’s relative obscurity is the real danger that his hypersensitive work will be allowed to disappear. “Jujol’s legacy is very quickly deteriorating. Not because it is being mistreated, but simply because, as he is not well-known, his buildings are not being cared for,” Miralles warns. One dramatic example is the parish church of Sant Feliu de Constantí, which had to be closed in 2016 as a precaution, with its roof collapsing last year.

“Only by promoting Jujol’s work will we ensure he’s appreciated and respected,” says Miralles. Getting to know and love Jujol as a way of conserving his work is the main idea of the new route that Miralles put together under the name: Territori Jujol, referring to Camp de Tarragona.

This open air tour comprises 16 sites, which apart from the four already mentioned include the Mare de Déu del Roser hermitage in Vallmoll, Casa Ximenis and the Gremi de Pagesos in Tarragona, Mas Carreras chapel and Sant Bartomeu church in Roda de Berà, the Mare de Déu de Montserrat sanctuary in Montferri, the Sant Jaume church in Creixell, the Santa Magdalena church in Bonastre, the Mare de Déu de Lloret hermitage in Renau and the Bràfim fountain, the Sant Salvador church in Vendrell, and the Sant Salvador church in Els Pallaresos.

It is an easy-to-do route, although it is worth remembering that advanced booking is required to visit many of these properties. The project’s website (www.territorijujol.com, which at the moment is only in Catalan but will also become available in Spanish and English) is probably the best place to start when planning a visit.

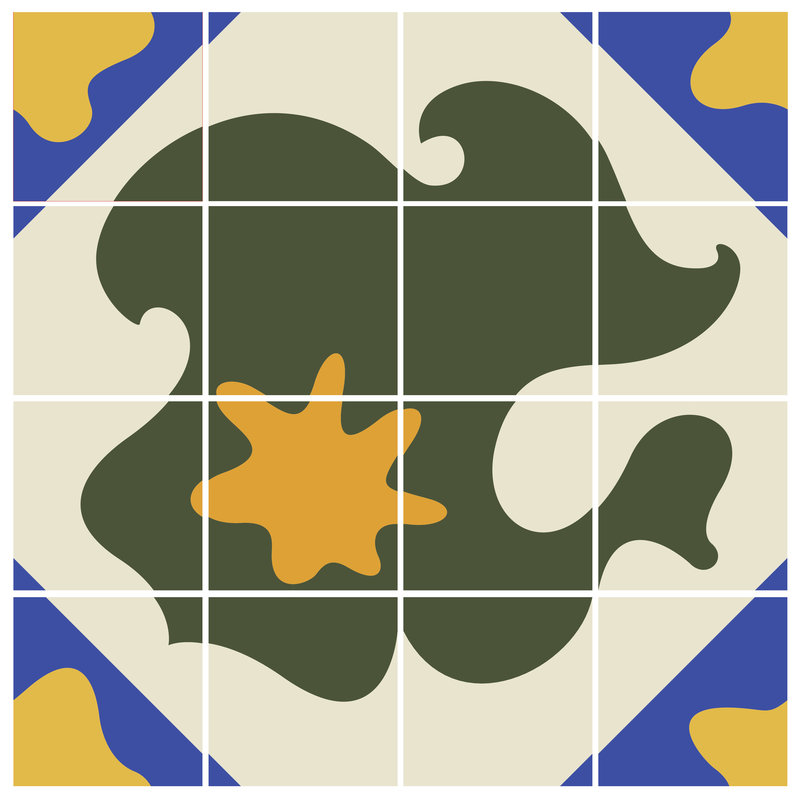

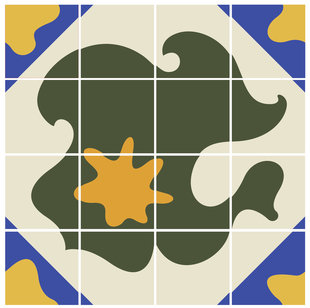

This tour through Jujol’s legacy reveals his origins, and his connection with the local landscape of Camp de Tarragona, from its birds to its dry-stone walls in a perfect fusion with the natural and rural world. In fact, this is to be seen in the logo and sign design for the route, designed by architect Guillem Colomer, who recovered a sketch of a hydraulic tile that Jujol never got round to producing, but which hints at the curved neck of a duck. Colomer split the design into 16 fragments, each piece representing a different site on the route, and together completing the jigsaw puzzle of the Territori Jujol project.

The jigsaw design is appropriate for Jujol’s work, which often lacked seriousness and his architecture has a significant playful element, often out of mere survival, as he often had to work with precarious resources. He would rely on local people to do the building as he could not always afford qualified workers, while he was often forced to use cheap or recycled materials.

Yet, it is this that contributes to Jujol’s modernity. “He is totally contemporary,” insists Miralles, especially at a time when the concept of erecting new work is just about forbidden. “We need to return to Jujol, to his idea of refurbishment, of working on top of what is already built, of not needing to finish work but to add to it over time to satisfy the needs at any one time: he spent 30 years on Casa Bofarull, and more than 20 on Mas Carreras…,” adds the expert.

Jujol achieved his architectural style without hardly leaving Catalonia. His only trip abroad was to Italy, when he was married in 1927. During the three-month trip, he was enchanted by the Renaissance and Baroque masterpieces he encountered. In particular, Bernini and Borromini were the artists he admired most, and that says art historian Immaculada Socias inspired his work on the Sant Salvador church in Vendrell.

feature

Drawing with both hands

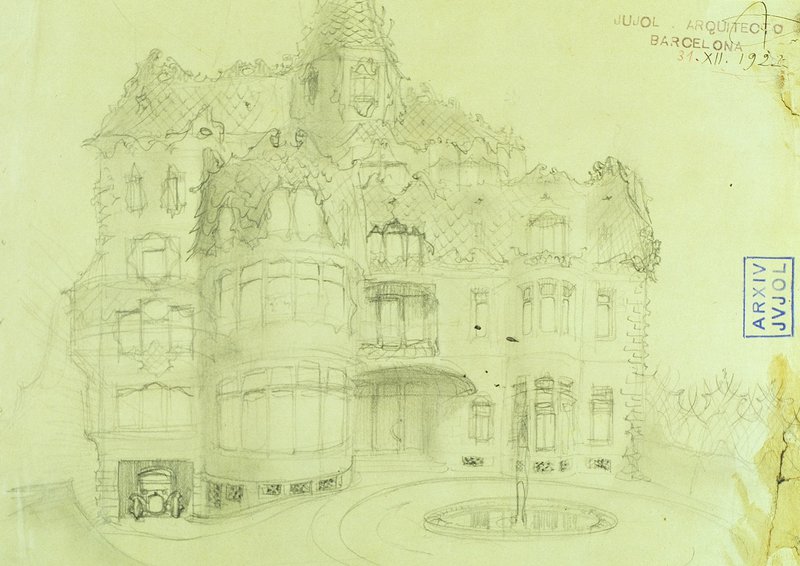

Jujol could draw with both hands at the same time. “He was super-gifted at drawing,” says architect Roger Subirà, curator of the exhibition at the Coac association of architects, which features 60 of Jujol’s drawings. Jujol i el dibuix shows the “creative incontinence” of an architect who could even express his ideas on a napkin, whether for a commission or just to amuse himself, making him “closer to an artist”. Not surprisingly for such a character, the work he left behind was “chaotic and disorganised”, says Subirà. A reason why exhibitions tend to use the same images, but Coac has gone deep into his archive to “dig up things that were hidden”. The exhibition has drawings from his time at school, as well as his early sketches for the Casa Planells project (pictured) linking Barcelona’s Diagonal avenue with Sicília street.