The cities of the future

By 2030, it is estimated that some 60% of the world’s population will live in large urban conurbations, making sustainability with the help of the latest technology one of the main challenges these areas face

The ‘La Ville du Quart d’Heure’ project is part of the initiative by Paris mayor Anne Hidalgo to improve the lives of city residents. The principle is that in less than 15 minutes a citizen should be able to access essential needs, from education and health to leisure and shopping. The idea is based on such things as the use of bicycles instead of polluting vehicles, the transformation of public spaces to give them multiple uses, or eliminating parking spaces to create green spaces or bicycle parking lots. Meanwhile, in April, Barcelona mayor Ada Colau presented a package of mobility measures that includes eliminating cars from over 21 kilometres of city roads in favour of bicycles, with an extra 30,000 square metres for pedestrians. To achieve this, the plan foresees such actions as closing the side lanes of Gran Via and Avinguda Diagonal to traffic, and widening the pavements of Via Laietana to 4.15 metres.

These are two examples of initiatives in line with the UN’s Sustainable Development Goals in the urban environment, which take as a baseline the impossibility of achieving sustainable development without radically transforming the way we manage cities. Since 2007, more than half of the world’s population has been living in cities and that number is expected to rise to 60% by 2030. Cities and metropolitan areas are nerve centres of economic growth and contribute some 60% of world GDP, but they also account for about 70% of global carbon emissions and more than 60% of resource use.

However, rapid urbanisation is resulting in an increasing number of people living in poor neighbourhoods, infrastructure and services (such as waste collection and water and sanitation systems, roads and transportation) that are inadequate and overburdened and that leads to more air pollution and uncontrolled urban growth.

The cities of the future will stand out for two reasons: their sustainability and their technology. For example, Songdo is a Korean city with more than 100,000 inhabitants 65 kilometres from the capital Seoul. Building on Songdo began from scratch in 2002 with the aspiration of it becoming the first smart and fully sustainable city in the world. To achieve this, the city is committed to the adoption of technology and urban planning that puts people at the centre. There is a predominance of mixed-use spaces, which bring together residential areas, services, leisure, and jobs. The distances between people’s houses and the other spaces have been calculated so that they can be covered on foot, and if you need to take public transport, there are metro and bus stops within a 12-minute walk from home.

Conventional cars, vans and lorries have been replaced by bicycles, while a pneumatic tube system removes waste. In addition, 40% of the city’s space is occupied by green areas, and most residential buildings are expected to recycle at least 40% of the water they use and store energy from renewable sources.

Masdar City is a green, self-sufficient city project designed by Norman Foster that began construction in 2008 next to Abu Dhabi Airport. Enclosed by a wall that protects it from storms and winds, it has a roof that reduces solar radiation and absorbs sunlight to produce electricity. It is energy self-sufficient, with a 10 megawatt photovoltaic plant, and non-electric vehicles are not allowed. Designed for 50,000 inhabitants, it has just over 2,000 residents and so far only 10% of it has been built. The idea is to create a destination attractive to technology companies in order to reduce the emirate’s economic dependence on oil.

Yet, the cases of Songdo and Masdar are exceptions, as most of the cities of the future will emerge from the evolution of existing ones. If there is one example of a metropolis where it looked as if collapse was inevitable but has managed to remedy the situation, it is Singapore. This Asian city-state, with 5.6 million inhabitants and a 7% growth forecast for 2030, has been ranked among the most sustainable urban areas in the world, based on strategic plans committed to optimising mobility and connectivity. It has fast public transport and acts as a test bed to develop mobility solutions that help reduce its dependence on cars. In addition, a network of sensors has been installed to measure pollution and the volume of traffic, to be able to react immediately in case of need. Even a system of 3D maps has been created to monitor the energy efficiency of each building, while hospital doctors have helper robots that are able to interact with humans.

As for the green issue, supertrees have been created, vertical gardens on steel structures between 25 and 50 metres high, which collect rain and are equipped with solar panels that generate electricity for night lighting and to cool two greenhouses that regulate the city’s temperature. The 24-storey block of flats known as the Tree House is the largest vertical garden in the world.

Smart cities

Singapore ranks first in the IMD Smart City 2019 Index, which focuses exclusively on how citizens perceive the scope and impact of efforts to make their cities smart, balancing economic and technological aspects with human dimensions. It is followed by Zurich, Oslo, Geneva and Copenhagen. The Danish capital aspires to neutralise its carbon footprint by 2025, as the country aims to achieve its independence from fossil fuels by 2050. One of the most basic tools used to achieve these goals is the bicycle, which is used in 50% of travel.

In terms of data and its use to improve the city, Copenhagen has launched the world’s first data marketplace. This offers public and private urban information of any kind to companies and citizens to develop smart solutions in any field. Among other advances, city residents can check the availability of parking in real time when major events are taking place. This is made possible by the fact that the city has a data exchange system between mobile phones, GPS devices installed on buses, and sensors located in places such as drains and bins. This system also makes it possible to study the mobility patterns of the inhabitants to adjust the city’s planning, increase safety and optimise the use of resources, as well as to regulate traffic in real time and reduce polluting emissions.

feature

New Urban Agenda

The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development adopted by the UN in 2015 includes goals that cities must have achieved within 10 years:

-Universal access to adequate, safe and affordable housing and basic services and to improve poor neighbourhoods.

-Access to safe, affordable, accessible and sustainable transportation systems and improve road safety.

-Reduction in the negative environmental impact of cities, paying special attention to air quality and waste management.

-Universal access to safe, inclusive and accessible green and public spaces.

-Support for economic, social and environmental links between urban, peri-urban and rural areas.

-Plans for resource efficiency and climate change mitigation.

The world’s most sustainable cities

London is the most sustainable city in the world, according to the 2018 Sustainable Cities Index (ICS), produced by the consulting firm that studies natural and built assets, Arcadis.

This index analyses 100 cities in three main areas: People (quality of life and social opportunities), Planet (energy use, pollution and emissions), and Profit (economy and the business environment). European cities – London, Stockholm, Edinburgh, Vienna, Zurich, Munich, Oslo and Frankfurt – occupy the first eight places in the top ten, with Singapore and Hong Kong completing the top ten. Only three US cities – New York, San Francisco and Seattle – are in the index’s top 20. African and Asian cities remain in low positions due to their poor rates of economic sustainability.

London is one of the few high-performing cities in the Arcadis index with relatively similar scores between the three key areas of sustainability, although the British capital still faces huge challenges associated above all with accessibility and congestion.

The report highlights the impact of the rapid launch of digital technologies on the relationship between the city and its people. Flood or superstorm resilience data, digitised utility bills, personalised mobility applications for Mobility as a Service (MaaS) are all cited as examples of successful urban digital tools.

Megalopolises

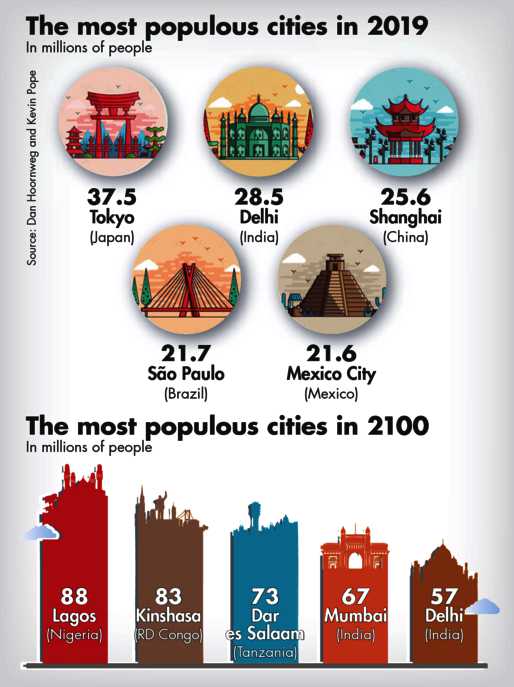

Tokyo is the largest megacity in the world, with 37.4 million inhabitants. In 2100, that distinction will pass to the capital of Nigeria, Lagos, with 88 million.

The concentration of the world’s population in large urban centres is a growing trend, because these cities are where much of the wealth is to be found. One of the consequences is that the number of megacities – cities with more than 10 million inhabitants – will multiply. In 2015, according to UN data, 54% of the population – about 3.69 billion people – lived in cities. By 2030, that will increase to 60%, accounting for more than 5 billion people.

Most of these megacities will be in emerging countries. In the medium term, that means Asian countries, such as China and India, and later African countries, such as Nigeria or Tanzania. Cities with more than 50 million people pose a huge challenge from the point of view of providing basic services and infrastructure. The construction of roads and underground rail systems can take decades to complete, and there is a danger of such infrastructure failing to keep pace with population growth.

Another challenge is climate change. Many of these megacities are located in coastal areas and depending on how environmental conditions evolve part of the territories in which they are located could end up underwater.

Growing vertically rather than horizontally

Increasingly more architects, such as those grouped around the NGO Vertical City, propose the concept of vertical cities. The idea is based on building skyscrapers more than 1,000 metres high, which would be interconnected and have all the services of a classic city: homes, offices, shopping and leisure centres, sports centres, gardens, transportation systems, and so on.

A vertical city would save up to 75% of the energy used by a conventional city, and reduce polluting emissions by up to 90%. The environment and the residents of these cities would benefit in many different ways, according to the proponents of the idea. A conventional horizontal city of 100,000 inhabitants generally covers an area of some four kilometres in diameter. However, a vertical city with the same number of residents would occupy an area of one kilometre in diameter, freeing up space for agriculture and green areas.

What’s more, consumption of natural resources such as water would be much more efficient in a vertical construction. and renewable energies, such as solar, wind, or geothermal energy, could be harnessed in such a way that they would reduce energy dependence on non-renewable sources.

Meanwhile, transportation would be another element of improvement. It is estimated that in a large city, a typical resident spends an average of two to four hours a day commuting. In vertical cities, workers would reside near their work, which they could reach on foot or with via internal transportation system, such as a lift or electric monorail.

One of the downsides of vertical constructions - apart from the visual impact on the landscape - is that the high number of storeys would make evacuation of the population more complicated in the event of an emergency.