TOP 10

The end of the world on your TV

Will the human species become extinct? Cinema has recreated all possible versions of pandemics and a post-apocalyptic planet. Now, Covid-19 is teaching us that reality can beat even the most fearsome fiction

Living through the end of the world on the front line from your sofa? We don’t know whether coronavirus will lead to the extinction of the human race – the climate emergency and greed might be better candidates for that – but we do know that we have been able to imagine and visualise it so far in thousands of ways thanks to the cinema, which has offered us a privileged seat to terrify us with all kinds of apocalyptic visions and catastrophes. Now we are all trying to digest from our homes the terrible news that comes to us every day, with the exponential increase in the number deaths, just as if it were a Hollywood script.

The American film industry especially has already brought this possibility to the big screen. As far as the pandemic that currently has us all confined to our homes is concerned, Contagion (2011) already predicted it with disturbing veracity. The Steven Soderbergh film reproduces, with almost with worrying similarity, what is happening worldwide with Covid-19. Alarming. Also in China, a bat transmits a lethal virus to a piglet that is devoured at a business dinner by Gwyneth Paltrow and company – by the way, the actress could not resist posting a photo of herself wearing a mask at the beginning of the health crisis. In Contagion, narrated in Soderberg’s classic documentary style, which gives greater credibility to the story, some 25 million people end up dying until a vaccine is found by Dr Cheever, a type of Fernando Simón in the film, played by Laurence Fishburne.

A few years earlier, in 1995, Wolfgang Petersen offered us a similar vision of a pandemic, which was also disturbingly realistic, in Outbreak. In this blockbuster, the possibility of human extinction becomes relatively real and believable again, with television cameras and the army following Dustin Hoffman during his search for the mythical patient zero. An enigma, by the way, that in the case of Covid-19, the Chinese have not yet been able to resolve. In this film version of Ebola, a monkey carries from Zaire to California a deadly hemorrhagic virus, and though with more Hollywood license than in Contagion, it brings us closer to the belief that the exponential spread of a disease without a cure can be devastating in a very short time. There are no shortage of moral doubts, in this case from the army, who decides who lives and who dies, and it poses the question of what a lesser evil means. According to the videos of nurses from Madrid that have gone viral on social media, the public healthcare system has been choosing for days which patients should be put on the precious ICU ventilators. Creepy. Of course, as a product of the American film industry, the protagonist is successful and prevents the disease from getting worse and finds a vaccine in record time. At least there’s a happy ending in this case.

The alien virus

In Invasion (2007), the second re make of the classic film The Invasion of the Body Snatchers (1956), the role of hero goes to a woman, Nicole Kidman, and the threat comes from beyond Earth. The virus is alien, and Kidman struggles to save her son, rather than the whole human race. The infection arrives through sleep and not even James Bond’s Daniel Craig is able to stop it. A terrifying pandemic ensues, which does not allow people to sleep. Imagine that happened in addition to what is going on these days? We couldn’t even enjoy one of the few pleasures that enforced quarantine allows us. In the original, a spectacular Donald Sutherland confronts the external threat, but without success. Once again in Invasion the American film industry allows us a happy ending, but with some final reflections and questions to take into account.

The quietest and most enigmatic pandemic erupted a year later in The Incident, from a master of intrigue and tension, M. Night Shyamalan. The proposal is again disturbing and obscure, as now humans, without knowing why, commit suicide collectively for no apparent reason. The phenomenon starts in Central Park, New York, and spreads to several cities in the eastern United States. An airborne toxin is the cause, and only a lucid science professor, Mark Whalberg, ends up finding the key to it: plants. The wind spreads the dangerous toxin among groups of people as if it were a coronavirus chasing the citizens at Mercadona in the midst of a tussle for the last of the valuable toilet paper supplies. Shyamalan’s narrative ability adds to his constant concern for the lack of knowledge about the origin of a completely invisible and asymptomatic enemy. In the end, Hollywood once again gives humans a second chance, albeit with a warning about what may come with climate change. It is terror with a message.

Those who had no second chance were the protagonists of other pandemics, already consummated in post-apocalyptic and totally devastated worlds. In Twelve Monkeys (1995), the few people who survived a lethal virus are living underground. Terry Gilliam tries to put the disaster right through the classic resource of travelling in time. A disoriented and ill Bruce Willis is in charge of finding out first what happened and then averting the disaster by returning to a past that does not exactly welcome him with open arms.

In The Road (2009) and The Book of Eli (2010) it all gets so much worse, because nothing can be fixed any more. In both films, the reason why the world came to its end is not clear. There is almost no one left and the plot is the day-to-day struggle of the protagonists in their attempt to survive in desolate and adverse conditions. Of course, there are important differences between the two films. In the first, perhaps the best post-apocalyptic film that has ever been made, the crudeness of everyday reality in a world without life, vegetation, or food, is masterfully evident. An immense Viggo Mortensen inflicts his suffering and that of his son on us without pity. The uncertainty about the future is complete, because there is no future. And, watch out, because in this post-apocalyptic world there is also, obviously, cannibalism. The photography is masterful, and the heavy dose of reality makes us think, for example, that it wouldn’t be wrong to lock up in some far away place all the bombs that still exist on the planet, and then throw away the key. Just in case.

The Book of Eli is much less cruel, and is closer to entertainment, in a production in which Denzel Washington shines. The infinite highways and giant bridges are still demolished, but now the search is more symbolic and metaphorical than anything else: preserving a Bible to bring redemption to the few remaining humans.

There is also a great deal of hope, redemption and faith in Children of Men (2006), by the Mexican director Alfonso Cuarón, which presents us with a dystopian future set in 2027 (not time much left for that), in which society is close to extinction due to a lack of human fertility. Men can no longer procreate and women have become sterile. In an environment of chaos, Clive Owen is charged with protecting the most precious asset on the planet: a refugee ready to give birth. The premise is interesting; the content of the film not so much, but the way it unfolds and the raw atmosphere makes it well worth watching.

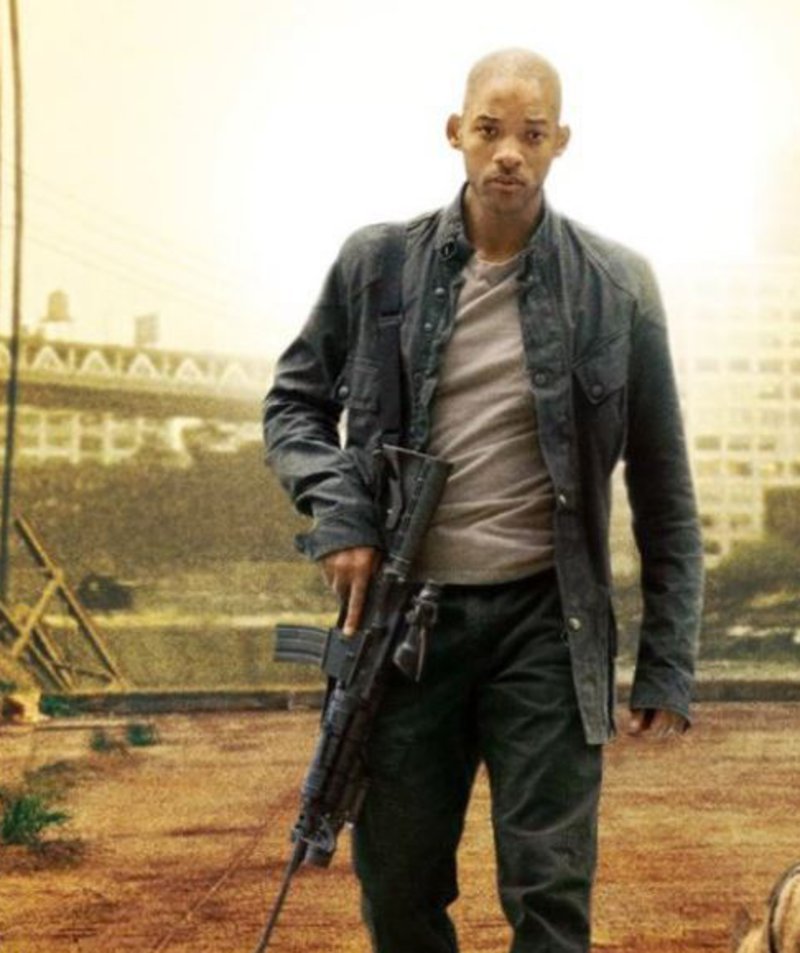

Less scientific is I Am legend (2007), which, pandemics aside, opens up a wide and wonderful world of killer zombies. In this remake of The Omega Man (1971), Will Smith replaces Charlton Heston as the last survivor on Earth. There is only one left, easy. Or so it seems. Dr Neville cannot prevent the expansion of a terrible man-made virus, originally created to eradicate cancer, which ends up mutating into a mega-pandemic. The truth is there are some survivors, though they have become zombies. It’s about the struggle for survival, not just being alone in an unknown and annihilated world, but also having to deal with new hostile enemies.

The zombie threat

It was the unforgettable Night of the Living Dead (1968), and its multiple remakes and versions, that was the first film to broach this theme. A scenario with contagious undead that we also saw in the excellent 28 Days Later (2002), from director Danny Boyle, followed by the no-less notable 28 Weeks Later (2007), directed by Juan Carlos Fresnadillo. Then came Infected (2009), by the brothers Àlex and David Pastor, the South Korean Train to Busan (2016), REC (2007), and the never-ending Resident Evil saga (2002).

Brad Pitt also joined the devastating and bloodthirsty zombie movie universe in World War Z. In this natural disaster, zombies take only 10 seconds to transform, and they are faster than usual, and very numerous. Seeing the current picture, we wouldn’t probably go wrong if Gerry Lane, the fictional virologist, could join Fernando Simon’s technical team, always surrounded and flanked by senior officials of Spain’s security forces. These really are a pandemic in themselves.

film

Gwyneth Paltrow and company – by the way, the actress could not resist posting a photo of herself wearing a mask at the beginning of the health crisis. In Contagion, narrated in Soderberg’s classic documentary style, which gives greater credibility to the story, some 25 million people end up dying until a vaccine is found by Dr Cheever, a type of Fernando Simón in the film, played by Laurence Fishburne.

A few years earlier, in 1995, Wolfgang Petersen offered us a similar vision of a pandemic, which was also disturbingly realistic, in Outbreak. In this blockbuster, the possibility of human extinction becomes relatively real and believable again, with television cameras and the army following Dustin Hoffman during his search for the mythical patient zero. An enigma, by the way, that in the case of Covid-19, the Chinese have not yet been able to resolve. In this film version of Ebola, a monkey carries from Zaire to California a deadly hemorrhagic virus, and though with more Hollywood license than in Contagion, it brings us closer to the belief that the exponential spread of a disease without a cure can be devastating in a very short time. There are no shortage of moral doubts, in this case from the army, who decides who lives and who dies, and it poses the question of what a lesser evil means. According to the videos of nurses from Madrid that have gone viral on social media, the public healthcare system has been choosing for days which patients should be put on the precious ICU ventilators. Creepy. Of course, as a product of the American film industry, the protagonist is successful and prevents the disease from getting worse and finds a vaccine in record time. At least there’s a happy ending in this case.

The alien virus

In Invasion (2007), the second re make of the classic film The Invasion of the Body Snatchers (1956), the role of hero goes to a woman, Nicole Kidman, and the threat comes from beyond Earth. The virus is alien, and Kidman struggles to save her son, rather than the whole human race. The infection arrives through sleep and not even James Bond’s Daniel Craig is able to stop it. A terrifying pandemic ensues, which does not allow people to sleep. Imagine that happened in addition to what is going on these days? We couldn’t even enjoy one of the few pleasures that enforced quarantine allows us. In the original, a spectacular Donald Sutherland confronts the external threat, but without success. Once again in Invasion the American film industry allows us a happy ending, but with some final reflections and questions to take into account.

The quietest and most enigmatic pandemic erupted a year later in The Incident, from a master of intrigue and tension, M. Night Shyamalan. The proposal is again disturbing and obscure, as now humans, without knowing why, commit suicide collectively for no apparent reason. The phenomenon starts in Central Park, New York, and spreads to several cities in the eastern United States. An airborne toxin is the cause, and only a lucid science professor, Mark Whalberg, ends up finding the key to it: plants. The wind spreads the dangerous toxin among groups of people as if it were a coronavirus chasing the citizens at Mercadona in the midst of a tussle for the last of the valuable toilet paper supplies. Shyamalan’s narrative ability adds to his constant concern for the lack of knowledge about the origin of a completely invisible and asymptomatic enemy. In the end, Hollywood once again gives humans a second chance, albeit with a warning about what may come with climate change. It is terror with a message.

Those who had no second chance were the protagonists of other pandemics, already consummated in post-apocalyptic and totally devastated worlds. In Twelve Monkeys (1995), the few people who survived a lethal virus are living underground. Terry Gilliam tries to put the disaster right through the classic resource of travelling in time. A disoriented and ill Bruce Willis is in charge of finding out first what happened and then averting the disaster by returning to a past that does not exactly welcome him with open arms.

In The Road (2009) and The Book of Eli (2010) it all gets so much worse, because nothing can be fixed any more. In both films, the reason why the world came to its end is not clear. There is almost no one left and the plot is the day-to-day struggle of the protagonists in their attempt to survive in desolate and adverse conditions. Of course, there are important differences between the two films. In the first, perhaps the best post-apocalyptic film that has ever been made, the crudeness of everyday reality in a world without life, vegetation, or food, is masterfully evident. An immense Viggo Mortensen inflicts his suffering and that of his son on us without pity. The uncertainty about the future is complete, because there is no future. And, watch out, because in this post-apocalyptic world there is also, obviously, cannibalism. The photography is masterful, and the heavy dose of reality makes us think, for example, that it wouldn’t be wrong to lock up in some far away place all the bombs that still exist on the planet, and then throw away the key. Just in case.

The Book of Eli is much less cruel, and is closer to entertainment, in a production in which Denzel Washington shines. The infinite highways and giant bridges are still demolished, but now the search is more symbolic and metaphorical than anything else: preserving a Bible to bring redemption to the few remaining humans.

There is also a great deal of hope, redemption and faith in Children of Men (2006), by the Mexican director Alfonso Cuarón, which presents us with a dystopian future set in 2027 (not time much left for that), in which society is close to extinction due to a lack of human fertility. Men can no longer procreate and women have become sterile. In an environment of chaos, Clive Owen is charged with protecting the most precious asset on the planet: a refugee ready to give birth. The premise is interesting; the content of the film not so much, but the way it unfolds and the raw atmosphere makes it well worth watching.

Less scientific is I Am legend (2007), which, pandemics aside, opens up a wide and wonderful world of killer zombies. In this remake of The Omega Man (1971), Will Smith replaces Charlton Heston as the last survivor on Earth. There is only one left, easy. Or so it seems. Dr Neville cannot prevent the expansion of a terrible man-made virus, originally created to eradicate cancer, which ends up mutating into a mega-pandemic. The truth is there are some survivors, though they have become zombies. It’s about the struggle for survival, not just being alone in an unknown and annihilated world, but also having to deal with new hostile enemies.

The zombie threat

It was the unforgettable Night of the Living Dead (1968), and its multiple remakes and versions, that was the first film to broach this theme. A scenario with contagious undead that we also saw in the excellent 28 Days Later (2002), from director Danny Boyle, followed by the no-less notable 28 Weeks Later (2007), directed by Juan Carlos Fresnadillo. Then came Infected (2009), by the brothers Àlex and David Pastor, the South Korean Train to Busan (2016), REC (2007), and the never-ending Resident Evil saga (2002).

Brad Pitt also joined the devastating and bloodthirsty zombie movie universe in World War Z. In this natural disaster, zombies take only 10 seconds to transform, and they are faster than usual, and very numerous. Seeing the current picture, we wouldn’t probably go wrong if Gerry Lane, the fictional virologist, could join Fernando Simon’s technical team, always surrounded and flanked by senior officials of Spain’s security forces. These really are a pandemic in themselves.

film