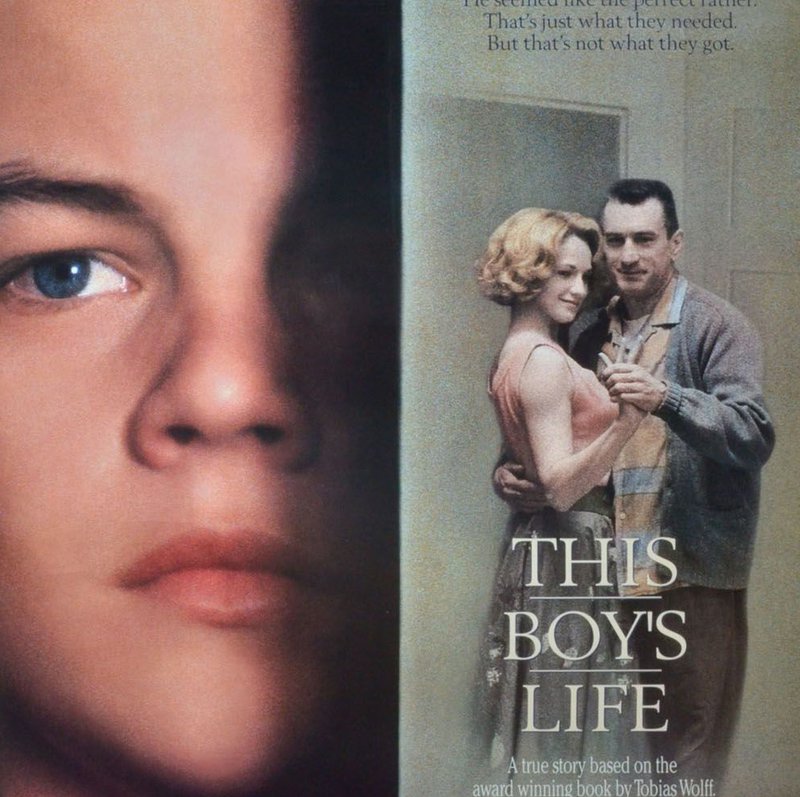

THIS BOY’S LIFE

It’s a great relief to read something as authentic as this memoir of Tobias Wolff’s childhood.

In 2018, when (even for adults) predictable superhero and action movies are dominating the western world’s popular culture as a form of escapism, my bowels were nicely warmed by having come across a one euro second hand copy of this little printed gem in Barcelona. It had been republished in 1994, seemingly given away with an end of year issue of ‘Esquire’, a North American men’s magazine.

I happily absorbed all the low-lights of the author’s young life in Concrete, a small company-town just south of the Canadian border, dominated by a cement factory. The reader learns that Jack (as he preferred to be called, after novelist Jack London) needed to drag himself through an upbringing that had all the underhandedness of Spain’s ultra-conservative government and the punishing violence of a month in Syria. Punches and kicks at school were the norm and sometimes the same at home with added insults from Dwight, an ornery stepfather who drank to excess whenever he had the money to indulge.

Like plenty of working class women of her era, Jack’s bright and capable mother is shown to be trapped in low paying jobs and a string of abusive relationships. In a sign of what is to come, she and Dwight come back early from their two-day honeymoon “silent and grim, not even looking at each other.”

One of the refreshing things about this autobiography is how honest Wolff is about his own character. With the perception of a fine mimic, he picks apart his family and friends but he also openly acknowledges how he uses lies to beef up his status with the locals and how he steals like a modern-day financier. Wolff even details the deceptive methods he employed to swindle his way into an (unsuccessful) scholarship interview for an expensive private high school.

Touchingly, the author also explains where he found relief from the daily grind of school and unending chores at home. Through music he gained some mental freedom and earning boy scout symbols provided a way to “compel respect, or at least civility from those who shared them and envy from those who did not.”

The official scout publications (where the book’s title comes from) Wolff read with the kind of fanaticism that is common in teenagers. “What I liked about [their] Handbook,” he remembers, “was its voice, the bluff hail-fellow language by which it tried to make being a good boy adventurous, even romantic.” The Scout Magazine he reads in a trance, “accepting without question its narcotic invitation to believe that I was really no different from the boys whose hustle and pluck it celebrated...Reading about these boys made me restless, feverish with schemes.”

As you can see, for a book that was first published in the late 1980s its language is pleasingly still rooted in a much earlier post World War II rural USA.

As well as this, Wolff’s work stands out to me because it examines a cross-section of American society that is still badly neglected in English language literature. Today, these are the same gun-carrying people who voted Donald Trump into the White House, in the hope of something better for their receding lives and now dead or dying industries.

In a recent interview, Tobias Wolff quoted Auden’s line that “writing an autobiography [is] like being a leper showing his sores in the marketplace.” He could just as easily have mentioned Flannery O’Connor, who argued that anyone who survives adolescence has enough material to write about.